366BC a young man joined Plato’s famous academy to learn about philosophy and the sciences. His name was Aristotle and he became Plato’s most successful disciple and a subsequent teacher at the academy. Aristotle is known today as a polymath and especially as a philosopher. He wrote about and studied subjects from physics, biology, over metaphysics and ethics to poetry.

During his lifetime he made a variety of groundbreaking contributions to the sciences, however, there was one that isn’t often recognized by people. One of his vast interests was a field his teacher Plato called “immoral, dangerous and unworthy of serious study”. It was the field of persuasion.

While Plato’s view on the subject was driven by an idealistic view of how the world and people should function, Aristotle was more focused on how these things actually did function.

Over the years Plato came to change his stance towards persuasion. He came to see its power and usefulness, as long as the tool was placed in the capable hands of a philosopher. This provided the starting point Aristotle needed to formalize the topic.

He wrote a treatise on the subject where he deconstructed what made something persuasive. “Rhetoric” was never intended for publication but rather a collection of his student’s notes from his lectures on the topic. With “Rhetoric” Aristotle laid the groundwork for persuasion studies in the west to this day.

But the conflict about the merits and ethics of persuasion didn’t stop there. Soon both the teacher and student found themselves on the same side facing a new persuasive enemy, the Sophists. The Sophists were teachers of young noblemen. They mostly taught philosophy and rhetoric. But in Plato’s eyes, their focus lied on deception and making arguments stronger without any merit through rhetorical means and tactics.

This ancient fight is still going on today and we can learn a great deal for ourselves tracing its steps. Through Aristotle’s insights into the persuasive arts we can ourselves become better speakers, writers, and leaders.

But let’s start at the beginning.

The three persuasive appeals

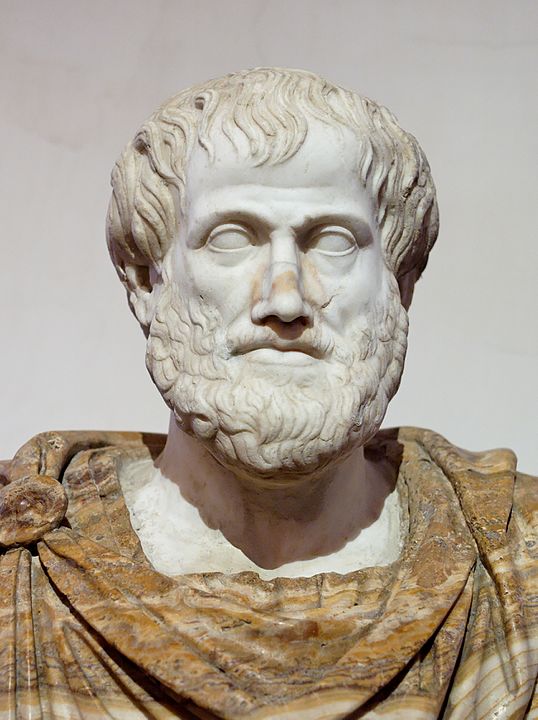

After Lysippos — Jastrow (2006), Public Domain

After Lysippos — Jastrow (2006), Public Domain

Aristotle identified three ways in which a speaker could persuade an audience. He called them ethos, logos, and pathos. Think of them as a persuaders toolkit. Only sticking to one of them severely limits your persuasive appeal.

Aristotle himself had a favorite one and at the end of this chapter you can probably guess which one it is. On which of the appeals you should focus on was also the core of the conflict between the Sophists and Plato’s school.

Even though the concept is more than 2000 years old it’s still equally valid. Most of modern persuasion research and practices can still be categorized in these three buckets.

Ethos

Are you credible? This is the central question of ethos. No matter if you write or speak, the persona you portray significantly impacts the believability of the argument. You have ethos if you can convey your expertise and trustworthiness to the audience.

But how can you convey your credibility?

Factors such as appearance, artifacts, and third-party opinions all increase your ethos and persuasive appeal.

Appearance: We are biased to judge people based on their appearance. It’s nothing short of a survival tool to identify potential threats quickly, but you can also use this bias to your advantage when persuading people.

If someone looks competent and trustworthy, we tend to judge them and their decisions more favorably. We say it takes a long time to build trust, but in reality, with the right clothes, behavior and smile, trust comes fast and cheap.

Don’t think appearance is only about clothing. In today’s world it’s also about your web and social media presence. All of these aspects form your public image, your persona, together with artifacts and third-party opinions.

Artifacts describe the various tangible things that show your ability. These include books you’ve written, projects you’ve completed, speeches you’ve done. Artifacts are valued very highly when people evaluate their credibility and competence. The reason is obvious because they’re hard to fake. While appearance can be easily adapted and changed, you cannot fake a successful project and work you’ve done. Everything you build and complete gives you credibility.

Third-Party Opinions: What people say about you matters a great deal. As a rule of thumb, people trust your claims less than other trustworthy people.

Of course, when you’ve built credible artifacts and have the right public persona you have a certain amount of credibility. But if everyone is talking shit about you people stay away, because there must be something wrong. Again, the principle behind it is the same as above, faking other people’s opinion of you is much harder to do, hence, it gives you more credibility –more ethos.

Of course, you can also convey expertise and trustworthiness through communicative means. For example, you can cite a third-party opinion about yourself. Donald Trump does this a lot. He does so either in an unspecified way or by citing specific people.

In an interview on Jimmy Kimmel in 2015 he used various ethos statements.

- “I’ve had so many people call me and say thank you.”

- “…you see people talking. They said, ‘Well, Trump has a point.’”

Or he cites people directly, as he did for a question regarding his tax plan during a primary debate.

- “Larry Kudlow, who I have a lot of respect for, loves my tax plan.”

Testimonials, reviews, or the What-people-say-about-this-book section on a book are all tactics of ethos. These tactics are incredibly powerful and used everywhere for two reasons. First, people must pay attention and listen to you in the first place. They’re simply more likely to do so if they think you are credible and helped other people. But secondly, it can even further strengthen your argument simply by making you appear an expert on the topic (even if you are, you have to convey it).

Logos

The persuasive appeal of Logos is judged by how reasonable an argument sounds. Logos is about the content of the message that is communicated. For everyone with an academic background this is the predominant appeal in all academic writing. When people think “this makes sense”, logos is at work.

However, don’t think Logos is hard logical proof. While some forms of Logos do use processes of formal reasoning others are just ways to make an argument sound more reasonable. The category of Logos includes a variety of figures of reasoning that can be used to increase the logical appeal of an argument.

Enthymeme: Aristotle called this “the strongest of rhetorical proofs”. There are different types of enthymemes but all of them are based on the classic three-part deductive argument.

- All men are mortal.

- Aristotle is a man.

- Therefore, Aristotle is mortal.

While using such deduction correctly is indeed a logical proof, in rhetoric things are often less clear.

Take for example the O.J. Simpson trial, where Simpson’s lawyer used an enthymeme that became famous:

“If the glove doesn’t fit, you must acquit.” — Attorney Johnny Cochran

The key is that there are hidden premises in such arguments that might or might not be true. The above argument includes the premise that there is only one possibility as to why the glove doesn’t fit, it’s not OJ’s. However, this is an implication thatignores all different explanations such as the shrinking of the gloves or enlargening of the hands through medicine for example. The problem is these premises are easy to miss and the audience might take the conclusion at face value.

Syllogismus: Not to be confused with the term “syllogism” from formal logic. In rhetoric, a syllogismus is not a formal proof but rather a tactic that provokes a conclusion through a visual remark. The conclusion in such arguments is implied and hence even stronger than if explicitly stated because the audience comes up with it ‘on its own’.

“Look at that man’s yellowed fingertips and you just tell me if he’s a smoker or not.”

Hypophora: Think of a classic rhetorical question but with one difference. Here the speaker raises a point and then immediately provides his answer. The key is that the speaker can choose which answer to give while the listener automatically thinks the objection eradicated. With such a device the speaker can choose the one answer — from the various possible explanations — that suits her intentions best.

“You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word: Victory. Victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror; victory, however long and hard the road may be, for without victory, there is no survival. “ — Winston Churchill

Pathos

Humans are irrational that is why pathos has immense power. Once you recognize that emotions are often more important than facts when it comes to convincing people, skills such as storytelling and stirring people’s emotions become important.

Passion is the driver of pathos in your speech and cannot be faked convincingly. If you don’t believe or feel the emotion you’re trying to invoke in other people, you’ll come across as phony and inauthentic. This is the death of persuasion. Hence, unless you’re a great actor, believing in your argument is essential.

Make it visual: Visually describing things will increase the emotional impact of the argument. This is because our brain automatically visualizes concepts and has difficulty visualizing abstract things. This is also the reason why abstract concepts are harder to remember. Using vivid and visual descriptions make it easier for the argument to develop its full emotional appeal.

The power of the right words: Words can frame things in a certain light and invoke emotions in the listener. Certain arguments have a stronger effect if the audience is feeling matching emotions. For example, raising points of additional security measures are much more powerful in a context where fear and insecurity dominate. In a state of fear we tend to listen to those offering security.

The fight of the ages

Aristotle and Plato were champions of Logos. It was the most important appeal in their eyes. Pathos on the other hand was equal with deception. An argument or discussion should not be fought over emotions but over concepts and truth.

In Plato’s eyes the Sophists were instructing their pupils on a way of rhetoric that was too much focused on pathos and what he thought as the art of deception. The age-old conflict of emotion vs. reason.

Who won?

For a long time it looked like Aristotle and Plato won in their appeal to Logos as the predominant factor in discourse. The age of enlightenment was all focused on this appeal and even today with the way science is dominating the world it seems to ring true.

However, I think it’s more nuanced than that. While Logos is a key component of rhetoric and thought, focusing solely on this appeal is severely limited. Simply look at today’s political landscape and you’ll inevitably see a focus on Pathos. Most speeches and discussions are conveyed on an emotional plane.

Polarising words filled with emotional coloring and passionate speeches are the norm. “An image says more than a thousand words” they say, and every teacher or marketer will tell you the same. Visuals are still more powerful than words and words that visualize more powerful than abstractions.

So while Aristotle and Plato’s cause for Logos as the predominant factor in the dialectic for truth is a noble and important one, it would be reductionist to ignore human nature and our affection for Pathos and emotional appeals.

In the end, Plato’s later opinion rings true, where rhetoric is a powerful and essential tool, as long as it was placed in the capable hands of a philosopher. Meaning that the motive, honesty, and message of the persuader are the deciding factors not the tactics used to convey it.

By Raphael — Stitched together from vatican.va, Public Domain